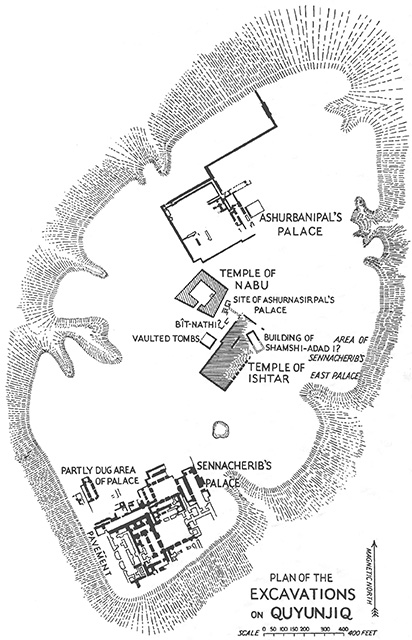

The Southwest Palace is so named due to its location on the Nineveh citadel mound of Kuyunjik (see the 1934 Campbell Thompson plan at the left, where it is labeled "Sennacherib's Palace" [Barnett et al. 1998:plate 5]; hover over to enlarge). It was first excavated by Austen Henry Layard in two campaigns between 1847 and 1851. It continued to be cleared through the late 1960s by a long list of archaeologists, but the palace has still not yet been fully uncovered or its layout fully understood. It seems from King Sennacherib's (704-681 BCE) inscriptions, that the palace was under construction between 701/2 and 694/3 BCE. When the Babylonians attacked and sacked Nineveh in 612 BCE, the palace was burned nearly completely. The once magnificent and plentiful wall reliefs and colossal guardian animals (mostly carved under Sennacherib, with some added by Ashurbanipal [668-627 BCE]) survive now only in their very lowest parts (Barnett et al. 1998;

Kertai 2015;

Reade 1998-2001:411-16;

Russell 1998:13-30,

1996,

1991;

Turner 2003).

The Southwest Palace is so named due to its location on the Nineveh citadel mound of Kuyunjik (see the 1934 Campbell Thompson plan at the left, where it is labeled "Sennacherib's Palace" [Barnett et al. 1998:plate 5]; hover over to enlarge). It was first excavated by Austen Henry Layard in two campaigns between 1847 and 1851. It continued to be cleared through the late 1960s by a long list of archaeologists, but the palace has still not yet been fully uncovered or its layout fully understood. It seems from King Sennacherib's (704-681 BCE) inscriptions, that the palace was under construction between 701/2 and 694/3 BCE. When the Babylonians attacked and sacked Nineveh in 612 BCE, the palace was burned nearly completely. The once magnificent and plentiful wall reliefs and colossal guardian animals (mostly carved under Sennacherib, with some added by Ashurbanipal [668-627 BCE]) survive now only in their very lowest parts (Barnett et al. 1998;

Kertai 2015;

Reade 1998-2001:411-16;

Russell 1998:13-30,

1996,

1991;

Turner 2003).

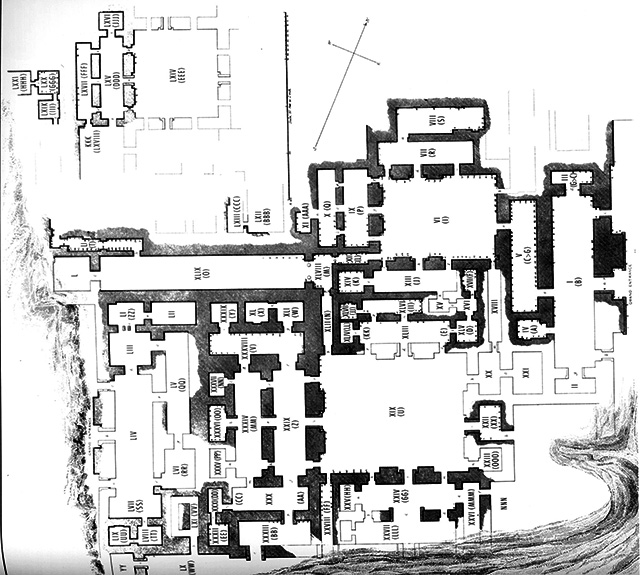

The Southwest Palace is Sennacherib's Palace without Rival, as he calls it in his texts inscribed on countless cylinders, prisms, bricks, sculptures, and thresholds. Though excavated for over 100 years, its architectural layout is still only partially understood (see Layard's 1853 plan at the left [Barnett et al. 1998:v.1 foldout]; hover over to enlarge). There is no fully agreed-upon accurate plan of the palace (see differing plans in, for example: Barnett 1998:v.2:plates 2-17; Kertai 2015:121-47; Reade 1998-2001:fig. 11). Based on Sennacherib's somewhat varying discussions of his construction process, the final complex was about 500m x 250m--immense, even by Assyrian standards.

The Southwest Palace is Sennacherib's Palace without Rival, as he calls it in his texts inscribed on countless cylinders, prisms, bricks, sculptures, and thresholds. Though excavated for over 100 years, its architectural layout is still only partially understood (see Layard's 1853 plan at the left [Barnett et al. 1998:v.1 foldout]; hover over to enlarge). There is no fully agreed-upon accurate plan of the palace (see differing plans in, for example: Barnett 1998:v.2:plates 2-17; Kertai 2015:121-47; Reade 1998-2001:fig. 11). Based on Sennacherib's somewhat varying discussions of his construction process, the final complex was about 500m x 250m--immense, even by Assyrian standards.

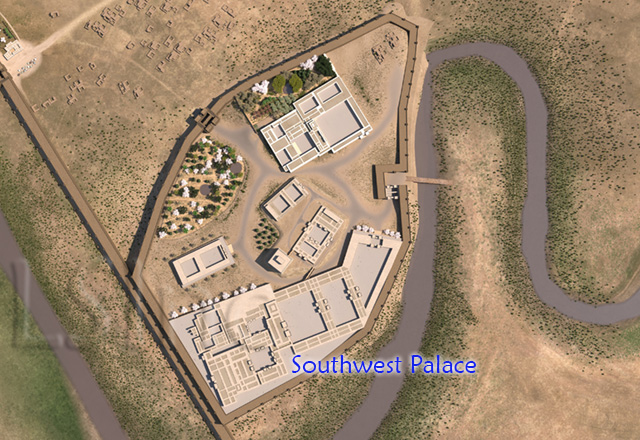

The overall layout of the palace complex follows Assyrian architectural traditions evolving since Ashurnasirpal II's grand Northwest Palace at Nimrud. There are several large courtyards that lead in toward the typical towered Throne Room facade, with three entries (the central one grander than the smaller side doorways) each flanked by colossal guardian animals, and with bas-relief sculpture between. The Throne Room suite fronts the domestic, ceremonial, and administrative quarters of the palace each set off by internal courtyards and corridors (Kertai 2015:185-29; Turner 1970). Among the inner chambers are the Ashurbanipal library and the Lachish battle reliefs room (discussed below). Our reconstruction of the palace (see an aerial rendering at the left with the palace oriented to roughly match the plan above; hover over to enlarge), which must still be regarded as tentative and incomplete, is based on discussions in the various sources listed below in the bibliography, personal conversations and emails with Assyriologists studying Assyrian palaces, and a synthesis of the most accurate plans, photographs, and drawings of the building.

The overall layout of the palace complex follows Assyrian architectural traditions evolving since Ashurnasirpal II's grand Northwest Palace at Nimrud. There are several large courtyards that lead in toward the typical towered Throne Room facade, with three entries (the central one grander than the smaller side doorways) each flanked by colossal guardian animals, and with bas-relief sculpture between. The Throne Room suite fronts the domestic, ceremonial, and administrative quarters of the palace each set off by internal courtyards and corridors (Kertai 2015:185-29; Turner 1970). Among the inner chambers are the Ashurbanipal library and the Lachish battle reliefs room (discussed below). Our reconstruction of the palace (see an aerial rendering at the left with the palace oriented to roughly match the plan above; hover over to enlarge), which must still be regarded as tentative and incomplete, is based on discussions in the various sources listed below in the bibliography, personal conversations and emails with Assyriologists studying Assyrian palaces, and a synthesis of the most accurate plans, photographs, and drawings of the building.

View the Learning Sites flyover and flythrough of the palace that shows the contextual location of fragments from Room 32 of the palace held in the collection of the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Atlanta.

The Lachish Battle Room contains wall reliefs devoted entirely to depicting the Assyrian advance on and destruction of the second largest city in the ancient Levant at the time, Lachish, and the aftermath of the battle. The attack took place in 701 BCE during the king's third military campaign, which saw him subjugate all the cities along the Phoenecian coast and those in Philistia and Judea (Millard 1985; Smith 1878:53-69). The episode is also recounted in the Bible (e.g., Isaiah 36:1-2, 37:8 and 2nd Kings 18:13-16).

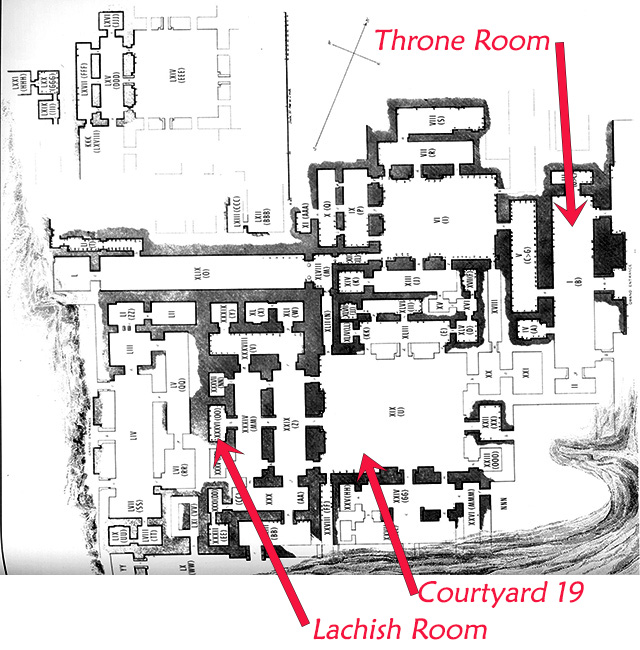

The Lachish Room (Room 36 according to Layard's numbering system) has a peculiar location within the Southwest Palace, especially given the dramatic subject of the reliefs, the consequences of the actions depicted, and the closely parallel biblical discussion of the battle and associated events around the region (notably the nearly simultaneous siege of Jerusalem). Clearly, the destruction and looting of the city was a key moment of the Assyrian king's military actions, and its timing with regard to events at Jerusalem makes the images that much more engaging. Yet, the battle at Lachish was deemed minor enough not to warrant mention in Sennacherib's annals or to be placed so as to impress palace visitors, since the battle narrative has been carved across a room deep inside the personal and administrative wing of the building, well away from public spaces (directly on axis with a corridor leading inward from the large inner Courtyard 19). Thus, as far as visiting dignitaries or tribute-bearers were concerned, the battle never happened. Yet, biblical chroniclers found the battle and its implications for Assyro-Judean relations crucial enough to discuss several times, in light of the nearly simultaneous Assyrian siege of Jerusalem.

The Lachish Room (Room 36 according to Layard's numbering system) has a peculiar location within the Southwest Palace, especially given the dramatic subject of the reliefs, the consequences of the actions depicted, and the closely parallel biblical discussion of the battle and associated events around the region (notably the nearly simultaneous siege of Jerusalem). Clearly, the destruction and looting of the city was a key moment of the Assyrian king's military actions, and its timing with regard to events at Jerusalem makes the images that much more engaging. Yet, the battle at Lachish was deemed minor enough not to warrant mention in Sennacherib's annals or to be placed so as to impress palace visitors, since the battle narrative has been carved across a room deep inside the personal and administrative wing of the building, well away from public spaces (directly on axis with a corridor leading inward from the large inner Courtyard 19). Thus, as far as visiting dignitaries or tribute-bearers were concerned, the battle never happened. Yet, biblical chroniclers found the battle and its implications for Assyro-Judean relations crucial enough to discuss several times, in light of the nearly simultaneous Assyrian siege of Jerusalem.

Still, someone carefully positioned the Lachish reliefs at the end of a long corridor framed with colossal guardian animals (see the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge) and precisely on axis with the center of the largest inner courtyard of the palace (see the aerial view above). Further, each successively inner set of colossal animals is slightly smaller than the previous accentuating the impression of perspective as one looks down the corridor toward the center panel, which shows the unfolding battle. Punctuating the view from the center of the administrative wing of the palace in this manner suggests that the king was more mistrustful of his staff and family than he was of enemies from outside. He used the narrative to show off his power and might to those supposedly closest and most loyal to him.

Still, someone carefully positioned the Lachish reliefs at the end of a long corridor framed with colossal guardian animals (see the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge) and precisely on axis with the center of the largest inner courtyard of the palace (see the aerial view above). Further, each successively inner set of colossal animals is slightly smaller than the previous accentuating the impression of perspective as one looks down the corridor toward the center panel, which shows the unfolding battle. Punctuating the view from the center of the administrative wing of the palace in this manner suggests that the king was more mistrustful of his staff and family than he was of enemies from outside. He used the narrative to show off his power and might to those supposedly closest and most loyal to him.

The Lachish battle scenes (a view of the room is at the left; from our 3D model of the palace; hover over to enlarge) are carved as if seen from the neighboring hilltop, most likely where Sennacherib set up his encampment. The panel's content is as follows:

The Lachish battle scenes (a view of the room is at the left; from our 3D model of the palace; hover over to enlarge) are carved as if seen from the neighboring hilltop, most likely where Sennacherib set up his encampment. The panel's content is as follows:

Barnett, Richard D.; Erika Bleibtreu and Geoffrey Turner

1998 Sculptures from the Southwest Palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh. London: Trustees of the British Museum, British Museum Press (2 vols.).

Kertai, David

2015 The Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2013 "The Multiplicity of Royal Palaces: how many palaces did an Assyrian king need?" pp.11-22 in David Kertai and Peter A. Miglus, eds., New Research on Assyrian Palaces. Heidelberger Studien zum Alten Orient v.15.

Layard, Austen Henry

1853 Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: J. Murray.

1849 Nineveh and its Remains. 2 vols. London: J. Murray.

Luckenbill, Daniel David

1927 Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, v.2 - Historical Records of Assyria. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

1924 The Annals of Sennacherib, OIP #2. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Millard, A. R.

1985 "Sennacherib's Attack on Hezekiah." Tyndale Bulletin 36:61-77.

Paterson, Archibald

1912 Assyrian Sculptures-- Palace of Sinacherib. The Hague.

Reade, Julian

1998-2001 "Ninive (Nineveh)," v.9, pp.388-433 in Erich Ebeling, Dietz Otto Edzard, Gabriella Frantz-Szabó, Bruno Meissner, Wolfram von Soden, and Ernst Weidner, eds. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Russell, John M.

1998 The Final Sack of Nineveh: the discovery, documentation, and destruction of King Sennacherib's throne room at Nineveh, Iraq. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press.

1996 "Nineveh," pp.152-70 in Joan Goodnick Westenholz, ed., Royal Cities of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Buble Lands Museum.

1991 Sennacharib's Palace without Rival at Nineveh. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Smith, George

1878 History of Sennacherib Translated from the

Cuneiform Inscriptions. London: Williams and Norgate.

Turner, Geoffrey

2003 "Sennacherib's Palace at Nineveh: The Primary Sources for Layard's Second Campaign," Iraq 65:175-220.

1970 "The State Apartments of Late Assyrian Palaces." Iraq 32.2:177-213.

Ussishkin, David

2014 Biblical Lachish: a tale of construction, destruction, excavation, and restoration. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

1982 The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Publications.