The impetus for our digital reconstruction of this ancient Assyrian capital was twofold: (1) Learning Sites was called upon to build accurate and detailed 3D models of the citadel, especially the so-called Southwest Palace of King Sennacherib for a series of videos produced by the Institute for the Visualization of History; the videos focus on the an inner room of that palace whose wall reliefs depict the destruction of the town of Lachish, a story also recounted in the Bible; and (2) the alarming and wanton destruction of the city walls, gates, and sculptural remains at Nineveh by ISIS/Daesh cannot be allowed to wipe this important site from the historical record.

The ancient Assyrian capital city of Nineveh, in northeastern Iraq, is located now within the modern Iraqi city of Mosul (the image at the left shows the state of the settlement from an RAF photo taken in 1929, kindly provided by Julian Reade, as compared to a GoogleEarth view from 2015; hover over to enlarge), about 240 miles (385km) northnorthwest of Baghdad. Nineveh was originally a separate walled settlement the outline of which can still be seen in both photos, straddling the Kosr River. The citadel mound of Kuyunjik at the northwest edge of the city held the palaces of King Sennacherib (704-681 BCE) and King Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE), the ziggurat, and an Ishtar Temple.

The ancient Assyrian capital city of Nineveh, in northeastern Iraq, is located now within the modern Iraqi city of Mosul (the image at the left shows the state of the settlement from an RAF photo taken in 1929, kindly provided by Julian Reade, as compared to a GoogleEarth view from 2015; hover over to enlarge), about 240 miles (385km) northnorthwest of Baghdad. Nineveh was originally a separate walled settlement the outline of which can still be seen in both photos, straddling the Kosr River. The citadel mound of Kuyunjik at the northwest edge of the city held the palaces of King Sennacherib (704-681 BCE) and King Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE), the ziggurat, and an Ishtar Temple.

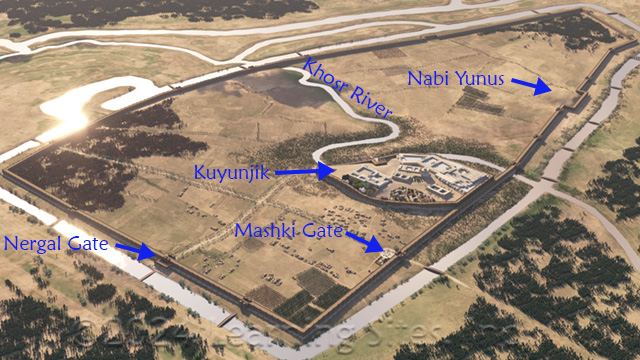

After Sargon II died in 705 BCE, his successor, Sennacherib, immediately moved the royal seat of the empire from Khorsabad to Nineveh, which had been an important urban center since the Middle Assyrian period (c.1300-900 BCE). Most likely, Sennacherib began his massive remodeling of the new capital before he departed on his third military campaign, during which he famously defeated the cities of the Levant and took siege of Jerusalem. He continued to improve Nineveh (soon home to over 100,000 inhabitants) by adding between 14 and 18 gates through the massive city wall (up to 25m thick), canals, bridges, aqueducts, gardens, parks, and roadways (see the aerial rendering at the left; from our 2016 model of the site; hover over to enlarge).

After Sargon II died in 705 BCE, his successor, Sennacherib, immediately moved the royal seat of the empire from Khorsabad to Nineveh, which had been an important urban center since the Middle Assyrian period (c.1300-900 BCE). Most likely, Sennacherib began his massive remodeling of the new capital before he departed on his third military campaign, during which he famously defeated the cities of the Levant and took siege of Jerusalem. He continued to improve Nineveh (soon home to over 100,000 inhabitants) by adding between 14 and 18 gates through the massive city wall (up to 25m thick), canals, bridges, aqueducts, gardens, parks, and roadways (see the aerial rendering at the left; from our 2016 model of the site; hover over to enlarge).

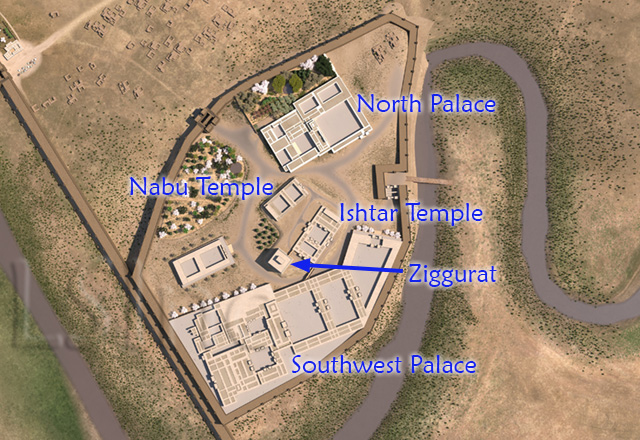

He dramatically rebuilt the citadel on the mound of Kuyunjik (see the aerial rendering at the left; from our 2017 updated model of the site; hover over to enlarge). His enormous "Palace without Rival", as he describes it throughout his inscriptions (the Southwest Palace as it's known today), crowns the citadel and displayed hundreds of carved bas-relief panels lining important rooms, colossal winged bulls guarding the major entryways, and lengthy texts telling all about his military and architectural achievements. Also on the hill are the ziggurat (the square building nearly in the center), the Ishtar Temple (near the Southwest Palace's outer courtyard), the Nabu Temple (near the corner of the North Palace), and the North Palace (expanded and rebuilt by Ashurbanipal in the mid- to late 7th c. BCE).

He dramatically rebuilt the citadel on the mound of Kuyunjik (see the aerial rendering at the left; from our 2017 updated model of the site; hover over to enlarge). His enormous "Palace without Rival", as he describes it throughout his inscriptions (the Southwest Palace as it's known today), crowns the citadel and displayed hundreds of carved bas-relief panels lining important rooms, colossal winged bulls guarding the major entryways, and lengthy texts telling all about his military and architectural achievements. Also on the hill are the ziggurat (the square building nearly in the center), the Ishtar Temple (near the Southwest Palace's outer courtyard), the Nabu Temple (near the corner of the North Palace), and the North Palace (expanded and rebuilt by Ashurbanipal in the mid- to late 7th c. BCE).

As early as 2014, but in earnest during the spring months of 2015 and 2016, the group known as ISIS/Daesh began systematically destroying the remains of the ancient city, including city walls, gateways, and unique sculpture. Much of the ancient capital city had remained intact for 2700 years, but fell easily to bulldozers, jackhammers, and dynamite. Videos of the purposeful elimination of crucial historical relics can be found online, but will not be repeated or linked to here. They are too painful to watch. Luckily, the site had been excavated off and on from the time Austen Henry Layard first discovered it in the 1840s, through the 1990s. We know a great deal about the city; many photographs have been published in printed reports and on online blogs and histories. That material (and discussions with Assyriologists) formed the basis of our digital reconstructions.

Layard, Austen Henry

1853 Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: J. Murray.

1849 Nineveh and its Remains. 2 vols. London: J. Murray.

Reade, Julian

1998-2001 "Ninive (Nineveh)." v.9, pp.388-433 in Erich Ebeling, Dietz Otto Edzard, Gabriella Frantz-Szab6, Bruno Meissner, Wolfram von Soden, and Ernst Weidner, eds. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

For additional resources, see the individual building pages.