Over the past 25 years or so, a growing body of evidence has surfaced to demonstrate that the ancient world was extremely colorful (certainly much more brilliantly decorated than Renaissance scholars would have liked us to believe). Everything from the Parthenon to Greek and Roman statues and even to the interiors of Assyrian palaces are now known to have been vibrantly painted. We make no judgments about ancient taste, but the polychromatic nature of ancient cities changes our perception of the past.

Selected Bibliography on Color in the Ancient World (NB: Research has blossomed since 2021, with publications too numerous to cite here`)

Brinkmann, Vinzenz; Renée Dreyfus & Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann

2017 Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor.

Brinkmann, Vinzenz; Oliver Primavesi & Max Hollhein

2010 Circumlitio: The Polychromy of Antique and Mediaeval Sculpture. Frankfurt am Main: Schriftenreihe der Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung.

Combs, Meghan

2012 "The Polychromy of Greek and Roman Art; An Investigation of Museum Practices," CUNY Academic Works. Masters Thesis, available online.

Nunn, Astrid; Barbara Jändl & Rupert Gebhard

2015 "Polychromy on Mesopotamian Stone Statues," Studia Mesopotamica: Jahrbuch für altorientalische Geschichte und Kultur 2:187-206

Østergaard, Jan Stubbe

2012 Tracking Colour: the polychromy of Greek and Roman sculpture in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Preliminary Report 4. Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

Østergaard, Jan Stubbe & Anne Marie Nielsen

2014 Transformations: Classical Sculpture in Colour. Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

Pollini, J.

2015 "Some observations on the use of color on ancient sculpture, contemporary scientific exploration, and exhibition displays," pp.901-10 in Patrizio Pensabene & Eleonora Gasparini, eds. ASMOSIA X: proceedings of the tenth international conference of ASMOSIA, Association for the Study of Marble et Other Stones in Antiquity, Rome, 21 - 26 May 2012. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider.

Learning Sites has been working on the 3D digital reconstruction of the Northwest Palace of the Assyrian king Ashur-nasir-pal II at Nimrud since 1997. It was then that Learning Sites president, Donald H. Sanders met with (the late) Samuel Paley and Alison Snyder during the annual conference of the Archaeological Institute of America, in NYC. The collaboration began with Paley, Snyder, and Richard Sobolewski's preliminary drawings of the throne room facade (see a preliminary sketch at the left; hover over to enlarge), in which they speculated about its proportions, doorway locations, reliefs, and room widths.

Learning Sites has been working on the 3D digital reconstruction of the Northwest Palace of the Assyrian king Ashur-nasir-pal II at Nimrud since 1997. It was then that Learning Sites president, Donald H. Sanders met with (the late) Samuel Paley and Alison Snyder during the annual conference of the Archaeological Institute of America, in NYC. The collaboration began with Paley, Snyder, and Richard Sobolewski's preliminary drawings of the throne room facade (see a preliminary sketch at the left; hover over to enlarge), in which they speculated about its proportions, doorway locations, reliefs, and room widths.

That new Learning Sites collaboration began to collect photos and drawings of the wall reliefs from the courtyard outside the throne room and for the throne room itself (and mapped those images onto our initial 3D model; see an early test rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge), in order to collocate the globally dispersed evidence into a single virtual world--for the first time. Prior to our attempt, many disconnected works on paper had to be manually shuffled to visualize each space. Our main goal was to envision what the throne room might have looked like from the point of view of an Assyrian standing in the space. The initial processes of collecting the data, making inferences about the size and construction of the room, and modeling the palace took many years to get to a point where we felt comfortable with our basic assessments.

The new virtual world allowed for entirely new lines of inquiry, ones that could not have been tried or even dreamed about when relying on traditional 2D media alone. New insight emerged about the circulation, lighting, sightlines, and propagandistic nature of the palace spaces; errors in the published hand-drawn reproductions of the throne room reliefs were also discovered. As the level of detail of our 3D model increased, we felt more comfortable adding color to the scene (mainly based on evidence from later palaces, especially those at Khorsabad), and then adding figures and furnishings (see the view east toward the throne at the left; hover over to enlarge).

These initial interpretations of the Northwest Palace throne room (and adjacent spaces) remained relatively unchanged for 20 years. More recently, when working with Julian Reade on related Assyrian buildings, citadel histories, and construction techniques, it became evident that it was time to re-evaluate our Nimrud throne room design. Rather than extrapolate from Khorsabad and related sites, enough data seemed available from excavated evidence, new analyses of pigments on Assyrian reliefs, and a total rethinking of the way palaces function. Four general categories of information concerning the Northwest Palace throne room were collected and analyzed: the construction and size of the room, evidence for a second tier of pictorial narrative above the carved reliefs, the background color of the walls, and the type and distribution of colors for the scenes, individual figures and trees, and decorative borders. Many, many references were studied over the course of the succeeding few years, including primary excavation notebooks and reports by Layard, Mallowan, Simpson, Wiseman, and al-Soof, among others (see the selected bibliography below), as well as evidence from several other Assyrian palaces and ancient cuneiform texts in which kings write about their buildings.

These initial interpretations of the Northwest Palace throne room (and adjacent spaces) remained relatively unchanged for 20 years. More recently, when working with Julian Reade on related Assyrian buildings, citadel histories, and construction techniques, it became evident that it was time to re-evaluate our Nimrud throne room design. Rather than extrapolate from Khorsabad and related sites, enough data seemed available from excavated evidence, new analyses of pigments on Assyrian reliefs, and a total rethinking of the way palaces function. Four general categories of information concerning the Northwest Palace throne room were collected and analyzed: the construction and size of the room, evidence for a second tier of pictorial narrative above the carved reliefs, the background color of the walls, and the type and distribution of colors for the scenes, individual figures and trees, and decorative borders. Many, many references were studied over the course of the succeeding few years, including primary excavation notebooks and reports by Layard, Mallowan, Simpson, Wiseman, and al-Soof, among others (see the selected bibliography below), as well as evidence from several other Assyrian palaces and ancient cuneiform texts in which kings write about their buildings.

Our initial thinking was that, since the Northwest Palace throne room is 10.45m wide, we would give the room a square section, making its ceiling height also 10.45m. Our new ceiling height for the throne room is 16m and was chosen based on more concrete reasoning. Loud and Altman place the ceiling height of Residence K at Khorsabad at a minimum of 14m. This was extrapolated from the size of the large (nearly completely preserved) painted panel that had fallen from the wall in that room (see the published reproduction at the left; hover over to enlarge). The excavators assumed that the panel had an arched top and calculated that it meant the room, which is about 8m wide, had a 14m height. Whether or not the panel actually had an arched top is debatable, but the 14m height would be reasonable in any case.

Our initial thinking was that, since the Northwest Palace throne room is 10.45m wide, we would give the room a square section, making its ceiling height also 10.45m. Our new ceiling height for the throne room is 16m and was chosen based on more concrete reasoning. Loud and Altman place the ceiling height of Residence K at Khorsabad at a minimum of 14m. This was extrapolated from the size of the large (nearly completely preserved) painted panel that had fallen from the wall in that room (see the published reproduction at the left; hover over to enlarge). The excavators assumed that the panel had an arched top and calculated that it meant the room, which is about 8m wide, had a 14m height. Whether or not the panel actually had an arched top is debatable, but the 14m height would be reasonable in any case.

In 1867, Place had estimated that primary palace rooms at Khorsabad had ceiling heights of 14-16m, based on an inscription of Sargon. Loud cites another inscription (see Luckenbill [from foundation deposits excavated in 1854]), in which Sargon discusses his palaces and says "its mighty walls...I made them...on top of 180 tipki (layers of brick)..." This thickness has been interpreted to be equal to 18m.

The primary throne rooms in the Northwest Palace and the palace at Khorsabad are comparable in size: Northwest Palace throne room--10.45m wide X 46m long; the Khorsabad throne room--11m wide X c.46m long. Since Residence K at Khorsabad was only the crown prince's throne room, we might expect that to be less grand than the king's throne room. If Room K is estimated to have been 14m, then using 16m for the king's throne room seemed reasonable.

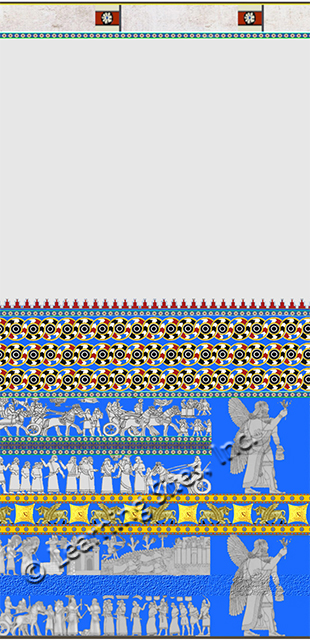

In general, the overall decorative composition for the walls of the throne room consists of the following elements (beginning at the floor and working upward): carved and painted stone bas reliefs (single figures, two long sequences of narratives separated by a band of cuneiform inscription, sacred trees, and two special scenes); decorative bands of painted decoration; sets of painted figures or scenes matching (in subject and height) similar figures or scenes below in stone; and a wide band of painted decorative designs capped by painted crenellations (see the snippet of the south wall at the left; hover over to enlarge). In particular (and using the throne room's south wall as an example), we have restored the specific features, figures, and scenes described below. Note that the west wall and east wall of the throne room present special cases, but their overall decorative scheme generally follows that depicted on the south wall. Note also that there is a special panel opposite the central doorway of the throne room that in its composition mimics the special panel behind the throne base on the east wall.

In general, the overall decorative composition for the walls of the throne room consists of the following elements (beginning at the floor and working upward): carved and painted stone bas reliefs (single figures, two long sequences of narratives separated by a band of cuneiform inscription, sacred trees, and two special scenes); decorative bands of painted decoration; sets of painted figures or scenes matching (in subject and height) similar figures or scenes below in stone; and a wide band of painted decorative designs capped by painted crenellations (see the snippet of the south wall at the left; hover over to enlarge). In particular (and using the throne room's south wall as an example), we have restored the specific features, figures, and scenes described below. Note that the west wall and east wall of the throne room present special cases, but their overall decorative scheme generally follows that depicted on the south wall. Note also that there is a special panel opposite the central doorway of the throne room that in its composition mimics the special panel behind the throne base on the east wall.

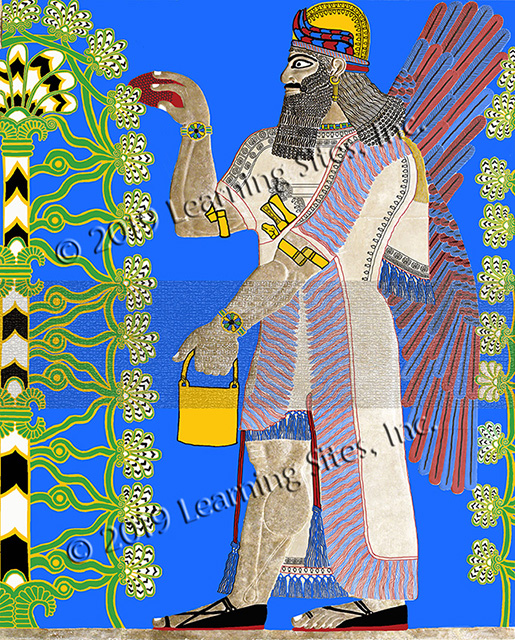

The lowest portion of the wall is covered with bas-relief panels carved from local Mosul limestone. The panels depict single figures, trees, or narrative scenes (usually in two long rows separated by a cuneiform inscription). The total height of these panels is about 2.25m. We now know that these reliefs were brilliantly colored (numerous chemical analyses have confirmed the range of colors and types of pigments used). Enough has been found, along with surviving color on the wall paintings from Til Barsib, and painted plaster and glazed brick from Ft. Shalmaneser (Nimrud), Khorsabad, and Nineveh, for us to extrapolate confidently about how the carvings in the Northwest Palace should be treated (see, for example, our colorization of a winged genius from Room S, at the left; hover over to enlarge).

The lowest portion of the wall is covered with bas-relief panels carved from local Mosul limestone. The panels depict single figures, trees, or narrative scenes (usually in two long rows separated by a cuneiform inscription). The total height of these panels is about 2.25m. We now know that these reliefs were brilliantly colored (numerous chemical analyses have confirmed the range of colors and types of pigments used). Enough has been found, along with surviving color on the wall paintings from Til Barsib, and painted plaster and glazed brick from Ft. Shalmaneser (Nimrud), Khorsabad, and Nineveh, for us to extrapolate confidently about how the carvings in the Northwest Palace should be treated (see, for example, our colorization of a winged genius from Room S, at the left; hover over to enlarge).

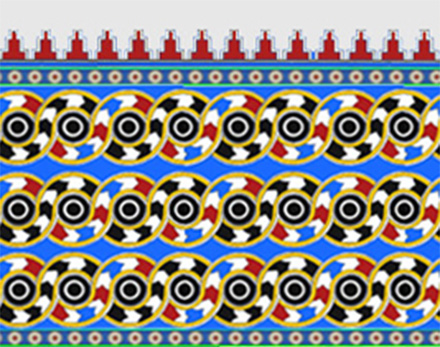

Above the stone reliefs was a decorative band of painted plaster c. 82cm high (matching the height of a single narrative register below; see image at left; hover over to enlarge). Given what was found and reproduced by Layard (and found in or around the throne room by other investigators), this decorative course consisted of knobbed plaques (called sikkate by the Assyrians, and also known as cushions or shields) alternating with kneeling bulls (in facing pairs), similar to painted scenes found by Layard and seen also at Til Barsib. This band is bordered, top and bottom, by rows of small rosettes and chevrons (again colored, sized, and spaced to match bits found and published by Layard and subsequent 20th c. excavators).

Above the stone reliefs was a decorative band of painted plaster c. 82cm high (matching the height of a single narrative register below; see image at left; hover over to enlarge). Given what was found and reproduced by Layard (and found in or around the throne room by other investigators), this decorative course consisted of knobbed plaques (called sikkate by the Assyrians, and also known as cushions or shields) alternating with kneeling bulls (in facing pairs), similar to painted scenes found by Layard and seen also at Til Barsib. This band is bordered, top and bottom, by rows of small rosettes and chevrons (again colored, sized, and spaced to match bits found and published by Layard and subsequent 20th c. excavators).

Above the sikkate band is a section of painted plaster the matches in figure type, tree location, and narrative scene composition (but not subject matter) the carved stone panels at floor level. The nature of the scenes and the types of figures are extrapolations from figural types, colors, and locations of many many bits of painted plaster found on the floor of the throne room by Layard and mid-20th c. excavators. The heights of the various elements of this wall section mirror those similar elements seen in the bas-reliefs below. The colors (blue, red, white, yellow) are based on the pigments of plaster fragments of people, horses, chariots, trees, and decorative motifs found on the throne room floor. In places where there are two narrower strips of narrative, they are separated here by a decorative band (instead of an inscription) comprised of rosettes, guilloche, and buds.

Atop all of this runs a triple guilloche (bordered by small rosettes). Such large and multiple rows of guilloche are found (as a triple band in Room F, adjacent to the throne room in the Northwest Palace, for example) and mentioned in Mallowan's notebooks from his 1952 clearing of the throne room floor. The guilloche here (scaled and colored to match those found in Room F) are capped by red crenellations, based again on decorative features found and recorded by Layard.

Atop all of this runs a triple guilloche (bordered by small rosettes). Such large and multiple rows of guilloche are found (as a triple band in Room F, adjacent to the throne room in the Northwest Palace, for example) and mentioned in Mallowan's notebooks from his 1952 clearing of the throne room floor. The guilloche here (scaled and colored to match those found in Room F) are capped by red crenellations, based again on decorative features found and recorded by Layard.

![]() The coloration of the sacred trees found at the corners of the room (an example from our throne room recolorization is at the left; hover over to enlarge) is based on a nearly complete, large similar tree of glazed brick discovered (in 1962 in Courtyard T) at Fort Shalmaneser, across the city from the citadel at Nimrud, and dated to the reign of Shalmaneser III, Ashur-nasir-pal II's son and successor. The green, yellow, black, and white are all preserved in the brick.

The coloration of the sacred trees found at the corners of the room (an example from our throne room recolorization is at the left; hover over to enlarge) is based on a nearly complete, large similar tree of glazed brick discovered (in 1962 in Courtyard T) at Fort Shalmaneser, across the city from the citadel at Nimrud, and dated to the reign of Shalmaneser III, Ashur-nasir-pal II's son and successor. The green, yellow, black, and white are all preserved in the brick.

There are other special panels and decorative nuances around the room, such as relief panels B-13 and B-23, one set in an shallow recess behind the throne and the other opposite the central door. These two vertical designs, which have their own set of features, are reconstructed based on evidence from around the room and other Assyrian palaces. The framing devices around and above doorways also have parallels from other sites.

Large expanses of blue paint were used as background to the various figures and scenes of the throne room wall. Lots and lots of cobalt blue had fallen to the throne room floor from all heights. The approximate find spots are mentioned in the 19th-century publications of Layard and in the excavation reports of Mallowan and al-Soof, especially, in the 1950s and 1960s. The 20th c. investigators discuss specific locations where they found fragments of blue paint and painted blue plaster, often in the company of painted figures and floral decorative details. Thavapalan discusses the various types of blues. A similar blue was found also at Ft. Shalmaneser at Nimrud and in the wall paintings at Til Barsib and Nineveh.

Based on all the documentation supporting our colored reconstruction of the throne room walls and similar types of evidence found throughout the Northwest Palace, we were able to colorize two other rooms--Room F (adjacent to the throne room and probably a preparation room for king before receiving visitors in the throne room) and Room S (the reception room of the king's personal quarters in the southern sector of the palace). Renderings from our work in those rooms appear on other pages herein.

al-Soof, Behnam Abu

1963 "Further Investigations at Ashur-nasir-pal's Palace" (unpublished manuscript).

Andrea, Walter

1923 Farbige Keramik aus Aussur und ihr Vorstufen in altassyrischen Wandmalereien. Nach Aquarellen von Mitgliedern der Assur-Expedition und nach photographischen Aufnahmen von Originalen im Auftrage der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft, Berlin: Scarabaeus-Verlag (especially for glazed tiles with designs similar to the Khorsabad Residence K painted panel).

Curtis, John

2013 An Examination of Late Assyrian Metalwork, Oxford: Oxbow Books (especially for photos and description of sikkate).

Layard, Austen Henry

1849 The Monuments of Nineveh from Drawings Made on the Spot. London: John Murray (especially for color plates of plaster fragments and designs).

Loud, Gordon & Charles B. Altman

1938 Khorsabad, part II -- the Citadel and the Town. Chicago: the University of Chicago Press.

Luckinbill, Daniel David

1927 Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, vol II, Historical Records of Assyria from Sargon to the End. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Mallowan, M. E. L.

1953 "The Excavations at Nimrud (Kalhu), 1952," Iraq 15.1:1-42.

1952 "The Excavations at Nimrud (Kalhu), 1951," Iraq 14.1:1-23.

Nunn, Astrid; Barbara Jändl & Rupert Gebhard

2015 "Polychromy on Mesopotamian Stone Statues: Preliminary Report," Studia Mesopotamica 2:187-206.

Paley, Samuel M.

1976 King of the World: Ashur-nasir-pal II of Assyria 883-859 B.C.. Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum (especially for photos of sacred trees with decorative detailing).

Place, Victor

1867 Ninive et l'Assyrie. Paris: Imprimerie impe´riale.

Reade, J. E.

1963 "A Glazed-Brick Panel from Nimrud," Iraq 25.1:38-47.

Sou, Li

2015 "Digital recolourisation and the effects of light on Neo-Assyrian reliefs," Antiquity Project Gallery 89(348). Available online.

Thavapalan, Shiyanthi; Jens Stenger & Carol Snow

2016 "Color and Meaning in Ancient Mesopotamia: the case of Egyptian blue," Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 106.2:198-214.

Tomabechi, Yoko

1986 "Wall Paintings from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud," Archiv für Orientforschung, 33:43-54.