After a prosperous period of stable rule in the early 1st century CE, Rome and its empire entered a time of conflict and uncertainty. Emperor Nero (54-68 CE), generally seen as a selfish ruler, was murdered in 68CE. Following his death, the empire fell into civil war which led to a succession of failed emperors before the general Flavius Vespasianus triumphed. Emperor Vespasian (69-79 CE) represented himself as a traditional peasant-soldier, who brought peace and stability to the realm. He had two sons (Titus [79-81 CE] and Domitian [81-96 CE]), who each succeeded him in turn as emperor. Altogether, the three comprised the Flavian dynasty. The three rulers looked to Rome's first emperor, Augustus (27 BCE - 14 CE), as their inspiration. Following Augustus' example, the Flavians similarly created peace after civil war and architecturally transformed the capital city.

According to the Roman historian and biographer Suetonius, Domitian was born on October 24, 51 CE in the 6th region of Rome, on the street called Pomegranate (most likely in the house of his uncle, since Domitian's father at the time was rather low on funds; indicated by the blue dot in the image at the left; hover over to enlarge). Domitian became successful in his military activities at the borders of the empire, especially in Britain. Within Rome, he was an active patron of the arts, literature, and Greek culture, and he also engaged in extensive architectural projects on a scale not seen since the time of Augustus. Yet his personal aggrandizement, assumption of divine powers, and representing himself as a god on earth doomed his reign and his reputation (not only throughout history, but beginning with tales about him told by contemporary writers, such as Tacitus and Pliny the Younger).

According to the Roman historian and biographer Suetonius, Domitian was born on October 24, 51 CE in the 6th region of Rome, on the street called Pomegranate (most likely in the house of his uncle, since Domitian's father at the time was rather low on funds; indicated by the blue dot in the image at the left; hover over to enlarge). Domitian became successful in his military activities at the borders of the empire, especially in Britain. Within Rome, he was an active patron of the arts, literature, and Greek culture, and he also engaged in extensive architectural projects on a scale not seen since the time of Augustus. Yet his personal aggrandizement, assumption of divine powers, and representing himself as a god on earth doomed his reign and his reputation (not only throughout history, but beginning with tales about him told by contemporary writers, such as Tacitus and Pliny the Younger).

Among the over 50 monuments erected by the Flavian dynasty in Rome are many well-known structures and many lesser-known and under-appreciated building complexes, such as: the Colosseum (also known as the Flavian Amphitheater), the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace), the Baths of Titus, the Arch of Titus, the Stadium of Domitian (whose shape became the Piazza Navona), the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Temple of Jupitor on the Capitoline, the Forum Transitorium, and the enormous palace on the Palatine Hill (some of the major monuments are indicated with red dots on the image at the left; hover over to enlarge). There is also the house in which Domitian was raised, discussed further below here.

Among the over 50 monuments erected by the Flavian dynasty in Rome are many well-known structures and many lesser-known and under-appreciated building complexes, such as: the Colosseum (also known as the Flavian Amphitheater), the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace), the Baths of Titus, the Arch of Titus, the Stadium of Domitian (whose shape became the Piazza Navona), the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Temple of Jupitor on the Capitoline, the Forum Transitorium, and the enormous palace on the Palatine Hill (some of the major monuments are indicated with red dots on the image at the left; hover over to enlarge). There is also the house in which Domitian was raised, discussed further below here.

Although we know from Suetonius about where Domitian was born, we know little else about the details of his family abode. However, recent excavations under the Caserma dei Corazzieri at #12 Via XX Septembre have revealed mosaics and inscriptions that indicate they belonged to Domitian's house. This further substantiates the implications from sculptural fragments found in the area that belonged to the family mausoleum built later on the same site by Domitian.

Much of the design, decoration, and furnishings for our reconstruction of Domitian's house (other than those from surviving remains) come from contemporary structures at the ancient cities of Pompeii, Oplontis, and Herculaneum, as well as depictions of period interiors from frescos at those sites (and with the assistance and guidance of staff at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, the Netherlands).

Based on excavations around Rome and throughout Pompeii (relating to materials, colors, building types and architectural features, and pavements), we have imagined a Flavian-era Pomegranate Street environment. There was nothing paricularly special about the thoroughfare, other than it happened to nurture an emperor.

Based on excavations around Rome and throughout Pompeii (relating to materials, colors, building types and architectural features, and pavements), we have imagined a Flavian-era Pomegranate Street environment. There was nothing paricularly special about the thoroughfare, other than it happened to nurture an emperor.

The grand portico (near the end of the street at the right on the image above; hover over to enlarge) that marked the house entrance lead inside through a vestibule of two spaces called the fauces. These rooms most likely had black and white mosaic floors and austere frescoed walls.

The grand portico (near the end of the street at the right on the image above; hover over to enlarge) that marked the house entrance lead inside through a vestibule of two spaces called the fauces. These rooms most likely had black and white mosaic floors and austere frescoed walls.

Once inside the house proper, visitors would enter the atrium (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge). This central open and airy space provided light and access to the major rooms of the house, as well as to the stairs reaching the upper stories. The main feature of the atrium is the central impluvium, a pool that collected rainwater from the roofs above and channeled them into drainage pipes leading away from the house. The positioning of the atrium allowed visitors to glimpse most of the main rooms of the house, as well as see axially through the house into the alternating dark and bright spaces toward the rear. Wall decorations were frescoes mainly of the 4th Style.

Once inside the house proper, visitors would enter the atrium (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge). This central open and airy space provided light and access to the major rooms of the house, as well as to the stairs reaching the upper stories. The main feature of the atrium is the central impluvium, a pool that collected rainwater from the roofs above and channeled them into drainage pipes leading away from the house. The positioning of the atrium allowed visitors to glimpse most of the main rooms of the house, as well as see axially through the house into the alternating dark and bright spaces toward the rear. Wall decorations were frescoes mainly of the 4th Style.

The tablinum was a space generally located between the atrium and the rear peristyle of ancient Roman houses and was often used to conduct the main business of the house (see the view at the left, looking back toward the atrium; hover over to enlarge). Domitian's tablinum was an airy space open to the breezes of the rear garden and with direct view of the main circulation spaces of the house. The walls are again painted with frescoes of the 4th Style, and the room is furnished with tables and benches for working on finances and family affairs.

The tablinum was a space generally located between the atrium and the rear peristyle of ancient Roman houses and was often used to conduct the main business of the house (see the view at the left, looking back toward the atrium; hover over to enlarge). Domitian's tablinum was an airy space open to the breezes of the rear garden and with direct view of the main circulation spaces of the house. The walls are again painted with frescoes of the 4th Style, and the room is furnished with tables and benches for working on finances and family affairs.

From the shaded colonnaded walkway around the peristyle, family members and visitors could access the tablinum, the grand nymphaeum, and the grounds behind the house.

From the shaded colonnaded walkway around the peristyle, family members and visitors could access the tablinum, the grand nymphaeum, and the grounds behind the house.

The peristyle garden at the rear of the house encompassed a central pool, elaborate plantings, less ornate frescoes, and an outdoor triclinium (a view of the three-couch dining area at the left; hover over to enlarge).

The peristyle garden at the rear of the house encompassed a central pool, elaborate plantings, less ornate frescoes, and an outdoor triclinium (a view of the three-couch dining area at the left; hover over to enlarge).

Off to one side of the peristyle garden was the colonnaded entry to the nymphaeum (visible in the view at the left; hover over to enlarge), a large dining space and imitation grotto. This is one detail of the house on Pomegranate Street that we can be sure existed.

Off to one side of the peristyle garden was the colonnaded entry to the nymphaeum (visible in the view at the left; hover over to enlarge), a large dining space and imitation grotto. This is one detail of the house on Pomegranate Street that we can be sure existed.

Remains of the original mosaics and some walls of the house's nymphaeum have come to light under the Caserma dei Corazzieri at #12 Via XX Septembre. We know the remains belonged to the house of Domitian, because the lead pipes there are inscribed with the name Flavius Sabinus, Domitian's uncle. Published photos and drawings of the decorations along with a partial reconstruction based on the finds (Cifani 2008) allowed us to re-create this spectacular space as well as hint at is original use (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge).

Remains of the original mosaics and some walls of the house's nymphaeum have come to light under the Caserma dei Corazzieri at #12 Via XX Septembre. We know the remains belonged to the house of Domitian, because the lead pipes there are inscribed with the name Flavius Sabinus, Domitian's uncle. Published photos and drawings of the decorations along with a partial reconstruction based on the finds (Cifani 2008) allowed us to re-create this spectacular space as well as hint at is original use (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge).

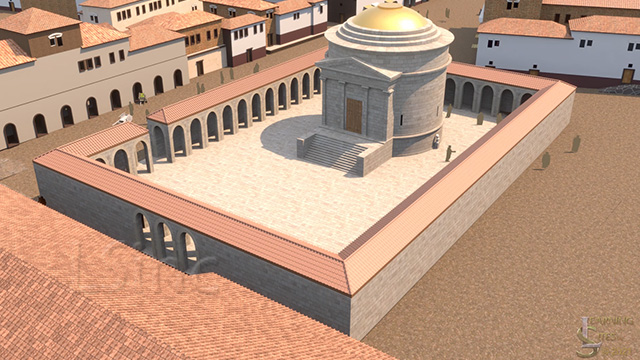

Contemporary ancient writers tell us that Domitian had the family mausoleum built around 94-95 CE on the site of the house in which he grew up on Pomegranate Street. The main structure of the Templum Gentis Flaviae (sort of a sanctuary for the family cult and a dynastic mausoleum) was round (view of our reconstruction at the left; hover over to enlarge). The large central structure was said to have been elevated on a podium and had a golden dome set into a large courtyard surrounded by a portico. All three Flavian emperors had their ashes buried there, and it survived into the mid-4th century CE. The so-called Hartwig-Kelsey sculptural fragments (and casts) belonging to the mausoleum are now housed in the Kelsey Museum (University of Michigan), other related pieces can be found in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Rome), and portrait busts of Vespasian and Titus (housed in the Archaeological Museum, Naples) were found also under or near the Caserma dei Corazzieri. These bits of evidence seem to confirm the location of the family burial complex (La Rocca 2009; Davies 2000; Dabrowa 1996).

Contemporary ancient writers tell us that Domitian had the family mausoleum built around 94-95 CE on the site of the house in which he grew up on Pomegranate Street. The main structure of the Templum Gentis Flaviae (sort of a sanctuary for the family cult and a dynastic mausoleum) was round (view of our reconstruction at the left; hover over to enlarge). The large central structure was said to have been elevated on a podium and had a golden dome set into a large courtyard surrounded by a portico. All three Flavian emperors had their ashes buried there, and it survived into the mid-4th century CE. The so-called Hartwig-Kelsey sculptural fragments (and casts) belonging to the mausoleum are now housed in the Kelsey Museum (University of Michigan), other related pieces can be found in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Rome), and portrait busts of Vespasian and Titus (housed in the Archaeological Museum, Naples) were found also under or near the Caserma dei Corazzieri. These bits of evidence seem to confirm the location of the family burial complex (La Rocca 2009; Davies 2000; Dabrowa 1996).

Carandini, Andrea

2017 The Atlas of Ancient Rome: biography and portraits of the city. Princeton: Princeton University Press (updated and reprinted by Cambridge University Press in 2015).

Amery, Colin & Brian Curran

2002 The Lost World of Pompeii. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press and Getty Publications.

Anderson, James C., Jr.

1983 "A Topographical Tradition in Fourth Century Chronicles: Domitian's building program," Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 32.1:93-105.

Bergmann, Bettina

1994 "The Roman House as Memory Theater: the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii," The Art Bulletin 76.2:225-56.

Capanna, Maria Cristina

2008 "Il Tempio della Gente Flavia sul Quirinale: un tentativo di ricostruzione," pp.1-8 in Workshop di archeologia classica : paesaggi, costruzioni, reperti 5. Fabrizio Serra Editore.

Cifani, Gabriele

2008 Architettura Romana Arcaica: edilizia e societa tra Monarchia e Repubblica, Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider.

Clark, John R. & Nayla K. Muntasser, Eds.

2019 Oplontis: Villa A ("of Poppaea") at Torre Annunziata, Italy. Volume 2: The Decorations: painting, stucco, pavements, sculptures. New York: American Council of Learned Socities Humanities e-book.

Cominesi, Aurora Raimondi; Nathalie de Haan; Eric M. Moorman & Claire Stocks, eds.

2021 God on Earth: Emperor Domitian. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 24. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Dabrowa, Edward

1996 "The Origin of the 'Templum Gentis Flaviae:' a hypothesis," Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 41:153-61.

Davies, Penelope J. E.

2000 Death and the Emperor: Roman imperial funerary monuments from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartnett, Jeremy

2008 "Si quis hic sederit: streetside benches and urban society in Pompeii," AJA 112.1:91-119.

La Rocca, Eugenio

2009 "Il templum gentis Flaviae," pp.271-97 in Lex de imperio Vespasiani e la Roma dei Flavi: atti del convegno, 20-22 novembre 2008 (Acta Flaviana #1). Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider.

Mau, August

1902 Pompeii: its life and art. London: MacMillan & Co.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42715/42715-h/42715-h.htm#Page_283

Packer, James E.

1971 The Insulae of Imperial Ostia, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 31.

Ulrich, Roger

2007 Roman Woodworking. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

https://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/galleries/Exhibits/Empire2/index.html

https://www.guidaturistica.roma.it/la-domus-della-gens-flavia-al-quirinale/

https://www.latinacittaaperta.info/2020/03/13/archeotour-il-mosaico-della-gens-flavia/

https://ilcantooscuro.wordpress.com/2018/02/10/templum-gentis-flaviae/