Nuzi (ancient kingdom of Arrapha, in Mitanni) is located in northeastern Iraq, near the modern town of Kirkuk. It was excavated by various American teams during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The site is marked by a low central mound whose habitation spans from the prehistoric era through the Mittanian / Middle Assyrian period (although there are scant remains of later occupations). It is from that last major occupation level that more than 5000 tablets were found that chronicle several generations of the local Hurrian population (from about 1435 to 1340 BCE). The texts cover the social, economic, religious, and legal customs of the inhabitants.

Could we devise new methods for how museums study and display their objects. This page collocates discussion and results of a collaborative photomodeling and CNC carving project undertaken in partnership with the Semitic Museum, Harvard University.

Although the museum is well known for its extensive textual archives, the problem put before LEARNING SITES did not concern their inscriptions. The issue focused on a pair of terracotta lions that probably once flanked a statue of the goddess Ishtar in a temple (so-called Temple G29, Stratum II) at the site of Nuzi. The lions were found smashed, most likely at the hands of the Assyrians who destroyed the city sometime between 1350 and 1300 BCE.

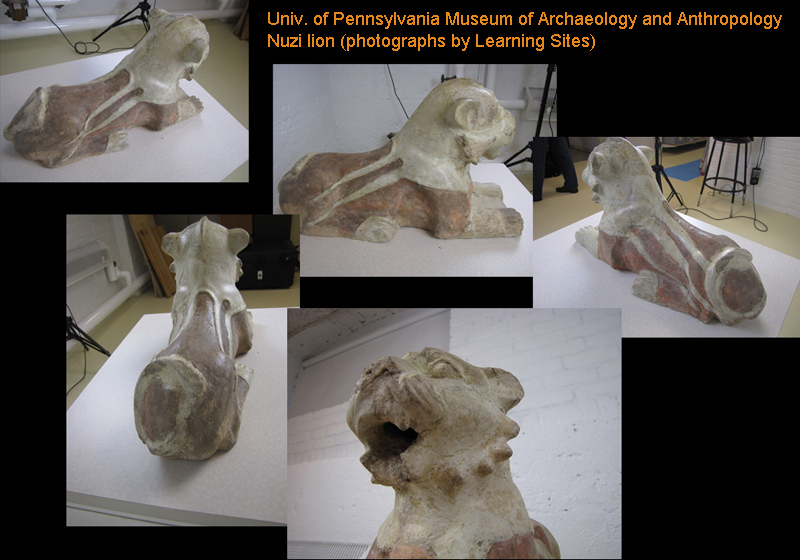

One of the lions (nearly complete, once its fragments had been reassembled; measuring c.27cm high, 47cm long, and 18cm wide; seen in the photo at the left; hover over to enlarge) belongs to the Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. It's made of buff ceramic partially covered with red paint and a greenish-blue glaze (now mostly gone).

One of the lions (nearly complete, once its fragments had been reassembled; measuring c.27cm high, 47cm long, and 18cm wide; seen in the photo at the left; hover over to enlarge) belongs to the Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. It's made of buff ceramic partially covered with red paint and a greenish-blue glaze (now mostly gone).

This lion had been on loan to the Semitic Museum at Harvard for the last 10 years (seen on display at the left; hover over to enlarge), so that it could join its mate on display. The Semitic Museum lion is not so well preserved--only the forepaws and hind quarters survive, but there is enough to make it clear that the two lions were created as a mirrored pair. The UPenn lion must be returned to Philadelphia.

This lion had been on loan to the Semitic Museum at Harvard for the last 10 years (seen on display at the left; hover over to enlarge), so that it could join its mate on display. The Semitic Museum lion is not so well preserved--only the forepaws and hind quarters survive, but there is enough to make it clear that the two lions were created as a mirrored pair. The UPenn lion must be returned to Philadelphia.

The imminent return of the UPenn lion created several problems:

LEARNING SITES innovative photomodeling and CNC carving techniques provided the solutions.

Photomodeling (creating accurate, detailed, and high-resolution 3D digital models from only photographs) frees museums from dependence on expensive laser scanners, continuous software upgrades, reliance on specialized personnel, and setting up specialized equipment (Assistant curator Adam Aja laying out the Semitic Museum's fragments ahead of the Learning Sites photo shoot; hover over to enlarge). Instead, high-quality 3D models can be created simply, efficiently, and cheaply from photographs taken with normal digital cameras (even from smartphone or tablet cameras). Although good lighting is an advantage, it is not necessary. Just point and shoot; collect a dozen or so shots from around the object; run it through our photomodeling software; and the result is a textured 3D model that can then be viewed in any number of interactive 3D environments, such as 3D pdfs or the Unity game engine.

Photomodeling (creating accurate, detailed, and high-resolution 3D digital models from only photographs) frees museums from dependence on expensive laser scanners, continuous software upgrades, reliance on specialized personnel, and setting up specialized equipment (Assistant curator Adam Aja laying out the Semitic Museum's fragments ahead of the Learning Sites photo shoot; hover over to enlarge). Instead, high-quality 3D models can be created simply, efficiently, and cheaply from photographs taken with normal digital cameras (even from smartphone or tablet cameras). Although good lighting is an advantage, it is not necessary. Just point and shoot; collect a dozen or so shots from around the object; run it through our photomodeling software; and the result is a textured 3D model that can then be viewed in any number of interactive 3D environments, such as 3D pdfs or the Unity game engine.

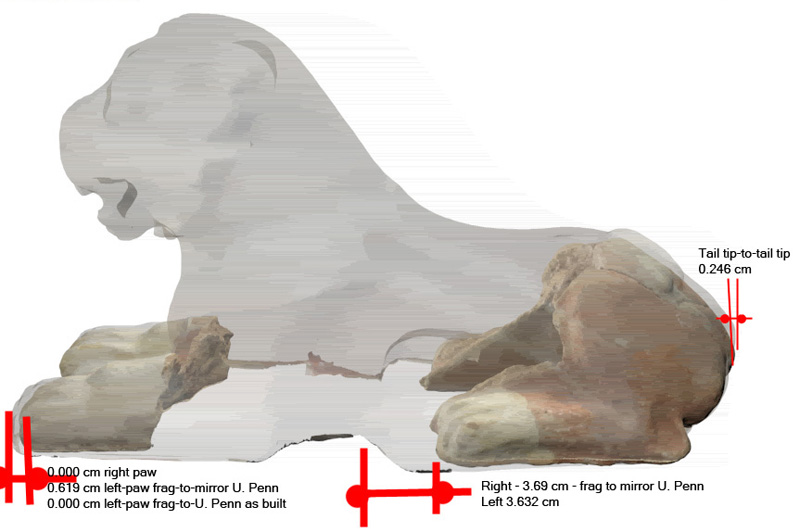

But photomodeling was only the beginning of the collaborative innovation. Once the 3D models were created, we could virtually compare the two lions by overlaying the computer models to see how closely they matched. It turns out that, unbeknownst to either museum, the two lions are quite different in size, even though their mirrored tails do align farily well. The overall size of the UPenn lion is larger than the comparable parts on the Semitic Museum lion (especially the size of the legs and paws). The screen grab (at the left; hover over to enlarge) from the 3D computer models of the two lions overlaid on top of each other to show the discrepancies in size and shape.

But photomodeling was only the beginning of the collaborative innovation. Once the 3D models were created, we could virtually compare the two lions by overlaying the computer models to see how closely they matched. It turns out that, unbeknownst to either museum, the two lions are quite different in size, even though their mirrored tails do align farily well. The overall size of the UPenn lion is larger than the comparable parts on the Semitic Museum lion (especially the size of the legs and paws). The screen grab (at the left; hover over to enlarge) from the 3D computer models of the two lions overlaid on top of each other to show the discrepancies in size and shape.

You can also see a short animation showing the differences in greater detail.

Once the computer models were completed, the next phase of the pioneering efforts could begin--3D printing so that each museum could own a complete set. Our 3D computer models were turned over to Neathawk Designs, who own a CNC (computerized numerical control) machine that could carve exact replicas of the lions in almost any material and to any scale. A sample 3/4 scale lion was created based on our 3D computer model the UPenn lion first, to test the printing process, the accuracy of the result, and the coloration that could be created. The lion was carved from low-density foam in sheets that were then glued together, coated with epoxy, and then painted (see the image at the left; hover over to enlarge).

Once the computer models were completed, the next phase of the pioneering efforts could begin--3D printing so that each museum could own a complete set. Our 3D computer models were turned over to Neathawk Designs, who own a CNC (computerized numerical control) machine that could carve exact replicas of the lions in almost any material and to any scale. A sample 3/4 scale lion was created based on our 3D computer model the UPenn lion first, to test the printing process, the accuracy of the result, and the coloration that could be created. The lion was carved from low-density foam in sheets that were then glued together, coated with epoxy, and then painted (see the image at the left; hover over to enlarge).

The next step was to virtually shrink the UPenn lion's 3D computer model so that the parts lined up with the smaller scale of the Semitic Museum's paws. With our computer models so adjusted and overlain, we could extract a 3D computer model of the missing sections that fit precisely into and among the paw fragments, providing the Semitic Museum with a complete lion so that visitors can appreciate how their pieces would have looked in sculptural context.

Legrain, Leon

1950 "The Babylonian Collection of the University Museum," University Museum Bulletin 10:3-4.

Online

Harvard Gazette (Dec. 4, 2012)

http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2012/12/an-ancient-statue-re-created/

Semitic Museum News (Nov. 29, 2012)

Time Magazine, Style Section (Jan. 30, 2013)

http://style.time.com/2013/01/30/harvard-uses-3-d-printing-to-restore-ancient-statue/#ixzz2JYO9VyN8

Wired Magazine (Dec. 10, 2012)

http://www.wired.com/design/2012/12/harvard-3d-printing-archaelogy/