A further refinement of the techniques Bill Riseman used back in 1992 for the Giza and Jebel Barkal models led to an understanding of how to utilize existing epigraphic information to reconstruct painted or carved hieroglyphics and then apply them onto the surfaces of a finished 3D computer model. To test this procedure, data from King Aspelta's tomb (ca. 600-580 BCE), in the Royal Cemetery of Kush, Nuri, Sudan, were used.

A further refinement of the techniques Bill Riseman used back in 1992 for the Giza and Jebel Barkal models led to an understanding of how to utilize existing epigraphic information to reconstruct painted or carved hieroglyphics and then apply them onto the surfaces of a finished 3D computer model. To test this procedure, data from King Aspelta's tomb (ca. 600-580 BCE), in the Royal Cemetery of Kush, Nuri, Sudan, were used.

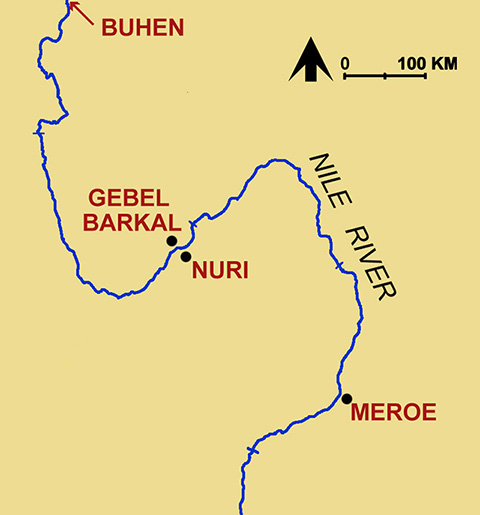

Nuri is located about 10km upstream and across the Nile River from Jebel Barkal. The granite sarcophagus of King Aspelta, however, is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The material for our work on this site was supplied by Timothy Kendall, then assistant curator at the museum.

The process of simulating the original hieroglyphics carved into a computer-generated granite sarcophagus took about an hour, once the research was completed. It had become increasingly clear to Riseman that the time and effort needed to create a digital reconstruction are not nearly as much as the time and energy required to research and study the archaeological evidence. Nevertheless, the reconstruction again demonstrated the power of the computer to bring together in a single model evidence scattered in different parts of the world and existing in varying states of preservation (the image at the left is from an animated flyover of the site; hover over to enlarge).

The process of simulating the original hieroglyphics carved into a computer-generated granite sarcophagus took about an hour, once the research was completed. It had become increasingly clear to Riseman that the time and effort needed to create a digital reconstruction are not nearly as much as the time and energy required to research and study the archaeological evidence. Nevertheless, the reconstruction again demonstrated the power of the computer to bring together in a single model evidence scattered in different parts of the world and existing in varying states of preservation (the image at the left is from an animated flyover of the site; hover over to enlarge).

The final reconstructed environment included accurate contour lines of the entire site taken from published topographic information. Once the model was completed, an animated sequence was created to lead the visitor around the site and funerary complex and then down into the tomb itself where the sarcophagus of the king could be seen in its original context complete with carved hieroglyphics fully restored.

The final reconstructed environment included accurate contour lines of the entire site taken from published topographic information. Once the model was completed, an animated sequence was created to lead the visitor around the site and funerary complex and then down into the tomb itself where the sarcophagus of the king could be seen in its original context complete with carved hieroglyphics fully restored.